How To Build a Stock Portfolio

%20-%20PNG%20-%2001-18-2022.png?width=1600&name=Image%20-%20Blog%20Image%20-%20Andy%20-%20What%20should%20I%20consider%20while%20building%20a%20stock%20portfolio%20-%20BuildingInspector%20(Color)%20-%20PNG%20-%2001-18-2022.png) Investing is complicated. There are almost infinite ways to build a portfolio of equities to fit your long-term financial plan. You can use a single catch-all fund, a handful of focused ETFs, individual stocks, a mix of all these, and more. For most of the equity accounts entrusted to our care, we use a mix of individual stocks and ETFs, with the stocks taking centerstage. Given that we take on the responsibility of managing such a portfolio, I am sometimes asked questions like:

Investing is complicated. There are almost infinite ways to build a portfolio of equities to fit your long-term financial plan. You can use a single catch-all fund, a handful of focused ETFs, individual stocks, a mix of all these, and more. For most of the equity accounts entrusted to our care, we use a mix of individual stocks and ETFs, with the stocks taking centerstage. Given that we take on the responsibility of managing such a portfolio, I am sometimes asked questions like:

- What is your investment philosophy?

- How do you choose investments?

- How do you trade?

We've answered these questions in our conference room (and recently on Zoom) many times over, but there isn't some secret sauce that we keep locked away. I thought I would write it down for more folks to read. Below is my list of things I think you need to do to build and maintain a good stock portfolio.

1. Practice High Humility

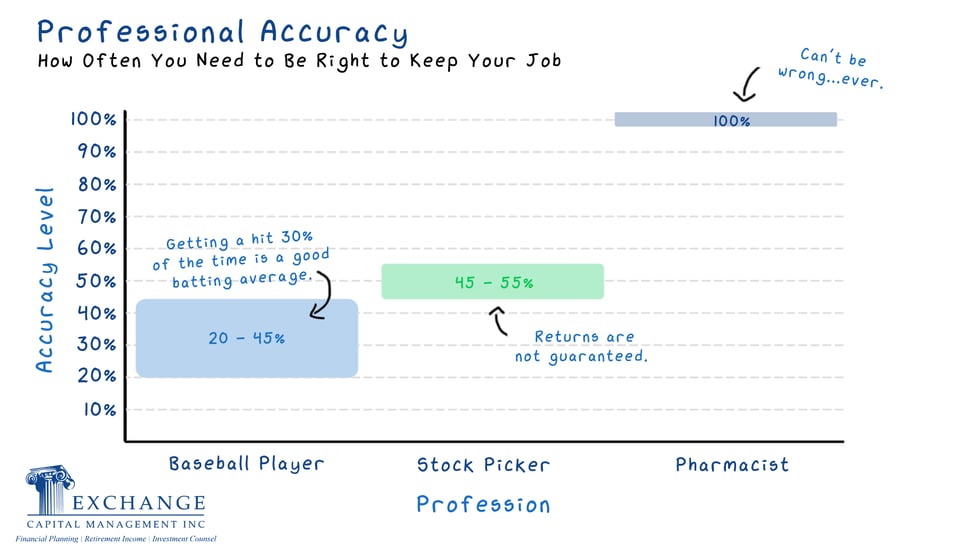

A few professions require non-stop perfection to be considered competent.

No one in investing has anything close to a perfect track record. Every portfolio manager has their list of wins and losses. The key is to recognize your mistakes and attempt to learn from them. To make matters worse, sometimes you make mistakes and still make money. When things go well, remember that there is a lot of luck in stock picking, and don't get too excited. Likewise, when things go poorly, remember the same, and don't be too hard on yourself.

2. Reject Hubris

If someone says they have a "sure thing" in the investment world, they are either lying or deluded. If you ever hear yourself saying this, you're in trouble.

3. Pay to Read Stuff from Folks More Focused Than You

Picking stocks is hard. It is impossible for one person to:

- Pay attention to the entire universe of stocks

- Pare that list down to companies worth a deeper dive

- Do the deeper dive

- Repeat forever

You need to either find some people who think about the investment world the way you do and read their work, or you will ignore large swaths of the market. I suggest the former. Find some research that meets as many of these qualifications as possible:

- Makes sense to you

- Has a consistent methodology over time and across the companies they cover

- You can afford

I try to find a team with a global methodology that is trainable, repeatable, and subject to peer review. This significantly diminishes the importance of the particular human doing the job. If your strategy relies on one or two particular analysts that are really good, they won't be selling you their research for long, they'll be launching their own hedge funds.

4. Focus on the Long Term

Even the best stock pickers don't time their investments perfectly. If you find a high quality company and you can buy it at a good price, don't worry about buying it on the perfect day. The goal is to make a significant profit in the long-term, and the pennies that you are worrying about now will seem silly.

5. Diversification

My parents told me, "Don't put all your eggs in one basket." Didn't yours?

6. Know What You Own

While diversification is good, you can go too far. While index replication strategies may produce results that are very close to an index, they also produce portfolios that are complicated and messy. Herein lies the problem: If you can't wrap your head around what's in your account, will you have the confidence to stay invested during the next market correction? Knowing what you own helps to reduce the chances that you will succumb to your emotions and push the eject button at the worst possible time.

7. Find Multiple Players for the Same Position

This can be difficult, especially in smaller industry groups, but try to find a handful of companies that do a good job in their world. This gives you options for diversification, swapping out players when needed, and allows you to compare their prospects and guidance. Build a watch list and keep an eye on it.

8. Think Probabilistically

There are no sure things. There are likely things and unlikely things, and all of those paths have outcomes at the end, some good and some bad. For example, profitable companies are more likely to outperform unprofitable ones, but sometimes unprofitable companies can have big runs in their stock price (ahem, GameStop?). The more you can build your plans to consider those paths of uncertainty and outcomes into the future, the better. You will be less surprised and more prepared for the bad possibilities.

9. Buy in Pieces

The chances of buying your stocks at the perfect bottom are nil. Spreading out your purchases over some time allows you ignore the short-term movements more easily.

10. Sell Your Losers (and Define Loser)

If things have gone wrong for a company and your original investment thesis has lost credibility, you must either re-write a new thesis or move on. There are plenty of other companies out there. Ask yourself, would I buy this company now if I didn't already own it? Don't let loss aversion stop you.

Now, imagine that a formerly great company has lost its way, but you're sitting on a large gain. The logic above still applies. Again, would you buy this company now? Don't let taxes stop you from selling and moving on.

11. Trim Your Winners

This is harder, but a very important selling rule. Let’s say you picked a company, put 3% of your portfolio into it, and then it went up 100% versus the rest of your portfolio. It has now become a 6% position. Go back to your investment thesis, practice your humility, and remember probabilistic thinking. Were you right or lucky? What do the future prospects look like? If you were buying this company for the first time now, would you allocate 6%?

If the answer to that last question is "No" and you still do nothing, you are ignoring the goal of diversification and ignoring other potential ideas for your portfolio. The cash to buy new names has to come from somewhere. Taking some profits off the table from a particular stock does not indicate weakness or fear.

12. Phone a Friend

Even after all the steps above, sometimes you just don't have a clear and actionable idea. For example, suppose you wanted exposure to the banking industry, but none of the individual companies stand above the rest? A fund can sometimes help plug a hole like that while you continue your research and wait for a player to show their worth versus the rest. Analyze the fund's investment process and holdings. Make sure it does what you want and isn't dominated by a bunch of names that you were already trying to avoid.

13. Never Go On Vacation

I am being a little facetious here. A long-term portfolio manager can ignore most daily movements and can take time to focus on other projects. However, the market doesn't care about your To-Do list. It can present a day-ruining event at any time. If you are on your own with your portfolio, this does make a real vacation difficult.

Whether you’re a doctor, executive, professor, business owner, or retiree, managing a portfolio takes time…a lot of time. You may have the skill and be willing to spend the effort needed to build a strong portfolio, but do you have the bandwidth to truly dedicate yourself to its continual management? After a careful look in the mirror, if you can confidently and honestly say that you do, use this guide as a blueprint and start building! If you find yourself questioning your ability or availability, it may make sense to buy back your time and work with an advisor that can help support you.

Andrew Stewart, CFA, CAIA is Chief Investment Officer and Partner at Exchange Capital Management, a fee-only, fiduciary financial planning firm. The opinions expressed in this article are his own.

Comments

Market Knowledge

Read the Blog

Gather insight from some of the industry's top thought leaders on Exchange Capital's team.

Exchange Capital Management, Inc.

110 Miller Ave. First Floor

Ann Arbor, MI 48104

(734) 761-6500

info@exchangecapital.com