The Price is Right: Stock Buyback Edition

.png)

When Andy was ten years old and in fifth grade, he discovered that if you strode confidently toward the bike rack at lunch time, the Hall Monsters (sorry, Monitors) would assume you had permission to go home to eat lunch with a parent. A few times that year, he used this method to hop on his bike, take his bag lunch to his empty home, and (sometimes with an accomplice) watch as much of The Price is Right as could fit into an elementary school lunch hour. Andy learned a few important lessons that year:

- Confidence and initiative are a powerful combination

- If you are unsure of the exact price of a thing, do your best to build a range of decent guesses before you bid

- When push comes to shove, bidding at the low end of your range leads to better outcomes over time

- We all have a responsibility to help control the pet population

Collectively, the West Wing at Exchange Capital Management has spent years studying architecture, engineering, finance, and mathematics, and we are all CFA charterholders or candidates. Sometimes, though, some educated guessing and intuitive logic can answer a complex question better (and faster) than quantitative analysis; just ask the contestants on The Price is Right. Given the recent revival of criticism toward corporate stock buybacks, we decided to walk through a thought experiment considering a simple question that is often ignored in the conversation.

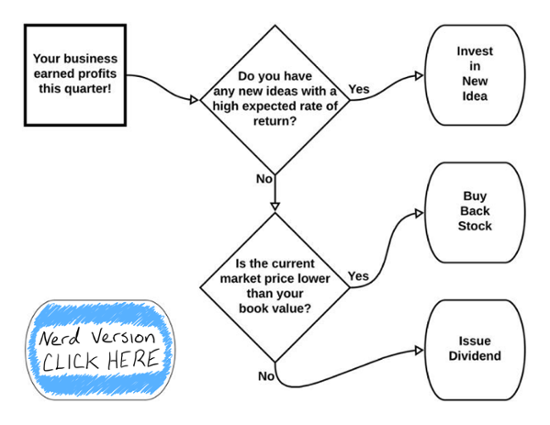

If you are a shareholder of a company that made a profit recently, what should you want them to do with those profits to best serve you? This is an old question that actually has a correct answer, assuming that all the stakeholders are knowledgeable and rational, and without taking taxes into account (simple assumptions, we know). Check out this handy flow chart to learn the answer!

The first thing a company should do with their profits is put them back into growing the business, assuming that the potential projects they have available are expected to earn a return higher than the company's cost of capital. If they do not have any projects that meet that standard, it makes sense to use the cash to pay back some of their capital. They could pay off debt, if they have any, or they can return cash to shareholders.

The first thing a company should do with their profits is put them back into growing the business, assuming that the potential projects they have available are expected to earn a return higher than the company's cost of capital. If they do not have any projects that meet that standard, it makes sense to use the cash to pay back some of their capital. They could pay off debt, if they have any, or they can return cash to shareholders.

If a company has decided to return cash to shareholders, how should they do it? There are two typical options:

- Dividends - Take the dollars you have available to pay and divide by the number of shares outstanding, write a check for that amount to each shareholder.

- Repurchase Equity - Buy back a portion of the outstanding stock, meaning future profits will have to be divided among fewer shares, which makes each share more valuable.

If the company's management team has a good handle on their business, they should have a reasonable estimate of how much they think their company's stock is worth. Given that they have that knowledge, logic would dictate that they should only repurchase their stock if the current market price is lower than that estimate. Many management teams would like to believe that their stock should always be worth more, but we can all think of an example of a company that traded well above its worth.

If the current market price is higher than the management team's internal estimate, the company should pay out a dividend. If the profits are expected to continue into the foreseeable future, consider paying out in a regular dividend that will recur every quarter/six months/year. If the profits are not expected to occur again or will be variable in size or timing, issue a special dividend. Given the constant volatility of stock prices, one could even argue that a good management team would shift between all these options: set aside a pot of cash to buy back stock whenever it happens to dip into the "cheap" zone, use new profits to refill that bucket, pay a dividend when the bucket overflows, cut back on dividend payments when the bucket totally empties.

Unfortunately, two problems get in the way of this easy decision-making process: irrational investors and taxes.

Irrational Investors: Some stock investors focus on dividend yield as the only measure of a stock's worthiness. This does not make a lot of sense, since growth is an important factor in equity investing, but these people are a part of the investing community, and they react badly when dividends go up and down in unpredictable ways. When these investors also use poor data sources that do not properly disclose which dividends are regular and which are special, the problem gets even worse. Furthermore, some investors will criticize special dividends, arguing that if the company was really doing well, it would have issued a regular dividend.

Generally, the investing public and the analyst community are more likely to criticize a management team over dividends than share buybacks. Buybacks are announced in advance with "up to" dollar amounts, execution occurs over time, and after-the-fact reporting on how much was purchased. Most people will not pay attention to how much of the stock the company said it might buy is then actually bought. Not many complain when the buyback last quarter was stated as "up to $0.55B" and this quarter is "up to $0.50B." On the other hand, many investors lose their mind when a company cuts its dividend by 10%. It is rational for management teams to avoid painful criticism from an irrational mob.

Taxes confound the relatively simple logic of the flow chart above in two ways: the timing of the tax and the amount of the tax.

Timing: Dividends are received by the investor and taxed in the year that the company decides to pay them. Capital gains, on the other hand, are paid when the investor decides to sell their stock, even if the profits were distributed via share buyback years earlier. The investor gets the cash when they want it, and it is taxed at that time. This is important, because the time value of money dictates that you should prefer to pay your taxes later. Plus, the embedded capital gain of an unsold stock goes away when you die, so if you can wait long enough, your heirs can avoid the tax altogether on your behalf.

Amount: Qualified dividends are taxed at the long-term capital gains rate for the receiver, so it might seem that investors are indifferent on this factor, but not everyone has the same rate. The rate ranges from 0% to 20%, roughly aligning with the income tax brackets. Then consider that the amount of stock owned in the U.S. by "the top [income] group [is] about nine times the size of mean holdings of the upper-middle income group," according to a 2016 Federal Reserve study.

So, there is an incentive for taxable owners of stock to prefer companies to distribute cash to shareholders via stock buybacks rather than dividends. This incentive is stronger for the wealthiest among us, whose capital gains tax rate is 20% versus 15% for most of us. The higher the tax bill, the more you want to delay it.

Even if smoke-filled rooms of Illuminati directing the CEOs of the Fortune 500 are a fantasy, the investor relations teams of these companies have the same data we do. A logical analysis would indicate that their investors would rather pay taxes later than sooner, especially the folks who own most of their company's stock. There is a healthy debate on which stakeholders should be highest on the CEO's list: shareholder, employee, community, environment, etc. We doubt many would place the Department of the Treasury at the top.

Unfortunately, it is likely that management teams ignore this thought experiment, and instead focus on satisfying their irrational investors as best they can (in an effort to keep their jobs). Slower growth companies that earn profits by making widgets have few new projects and pay regular dividends, because tradition! Faster growth companies that are inventing new widgets reinvest most of their cash in new ideas. They do a buyback when they have extra cash, because special dividends are frowned upon, regular dividends are too much responsibility, and their taxable investors prefer it. Many companies do both, but we wonder how many have a flow chart taped to their CFO's desk.

Who Wrote this Anyway? Who is The West Wing?The West Wing (our offices are at the west end of the building) is made up of three full-time professionals (Andy, Olivia, & Matt) who are charged with leading the firm's day-to-day investment and trading operations Andrew Stewart, CFA is a Senior Portfolio Manager, Olivia Stacey is a Portfolio Manager, and Matt Farris is a Trader at Exchange Capital Management, a fee-only, fiduciary financial planning firm. The opinions expressed in this article are their own. |

Comments

Market Knowledge

Read the Blog

Gather insight from some of the industry's top thought leaders on Exchange Capital's team.

Exchange Capital Management, Inc.

110 Miller Ave. First Floor

Ann Arbor, MI 48104

(734) 761-6500

info@exchangecapital.com